Takeaways

- Russian banking officials warn of a credible risk of a systemic banking crisis in the next 12 months due to a growing number of corporate and retail clients failing to make loan payments.

- Bad debt on Russian banks' balance sheets is estimated to be in trillions of rubles, with borrowers deferring payments, and the true magnitude of the debt problem may be masked by official figures.

- The economy is facing a worsening outlook, with a slowdown in growth, accelerating inflation, and labor shortages, which could raise questions about President Vladimir Putin's ability to sustain Russia's war in Ukraine.

Russia’s economy faces a worsening outlook that is graver than publicly acknowledged, with a credible risk of a systemic banking crisis in the next 12 months, according to Russian banking officials.

Russian banks are increasingly concerned about the level of bad debt on their balance sheets, according to the officials and documents seen by Bloomberg News. They have privately raised the alarm about the number of corporate and retail clients who are failing to make loan payments as they struggle with high interest rates, the people said.

Current and former banking officials have privately described the situation in Russia as dangerous and said there is a growing risk of a debt crisis spreading through the country’s financial sector in the next year if circumstances don’t improve. The people spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss publicly the anxieties within the sector.

Strains within the banking system could raise wider questions for President Vladimir Putin’s ability to sustain Russia’s war in Ukraine that’s already in its fourth year, especially if Kyiv’s US and European allies were to target the Russian financial sector with harsher sanctions. The European Union is currently discussing fresh restrictions on more Russian banks.

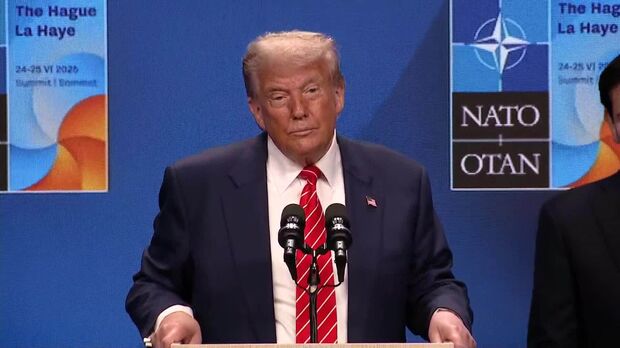

Ukraine’s supporters have also been pushing for Donald Trump to hit Russia with tough new sanctions after Putin rejected calls for a ceasefire in the war to allow for peace talks. So far, the US president has held off taking measures.

Official figures may mask the true magnitude of the debt problem, some of the people said. Borrowers are deferring payments, meaning that while public data on late payments don’t yet suggest a serious problem, the reality is that many more loans are not being repaid as planned, according to an internal note from one major bank seen by Bloomberg.

Banks have estimated that their bad debts run to trillions of rubles and are taking steps to manage the increased risk leading to early signs of a credit crunch, people familiar with the internal assessments said. One estimate showed that the corporate loan portfolio by Russian banks in the first two months of 2025 decreased by 1.5 trillion rubles ($19 billion) before stabilizing.

Tensions among Putin’s top officials over risks to the economy spilled into the open at the flagship St. Petersburg International Economic Forum last week.

“We are on the verge of slipping into a recession,” Economy Minister Maxim Reshetnikov said during a panel discussion in which Bank of Russia Governor Elvira Nabiullina argued the economy was experiencing a necessary cooling. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov acknowledged “we’re going through a cold spell now.”

Putin made his position clear in a speech the following day. “Some specialists, experts, point to the risks of stagnation and even recession,” he said. “This, of course, should not be allowed under any circumstances.”

To be sure, years of unprecedented sanctions by the US and its Group of Seven allies since Putin ordered the 2022 invasion have so far failed to bring Russia’s economy to its knees, as the government massively expanded spending on defense industries and to support businesses affected by the restrictions.

Russian banks also posted record profits of 3.8 trillion rubles in 2024, beating the year earlier result by 20%, according to central bank data.

The military’s demand for manpower intensified labor shortages, however, and helped drive a wage spiral that boosted the incomes of many Russians but also fueled accelerating inflation to an annual peak of more than 10% in the overheating economy.

The Bank of Russia responded by hiking its key interest rate to a record-high 21% in October. Nabiullina cautiously cut the key rate for the first time in nearly three years to 20% this month following a chorus of complaints from officials and businesses that punitive debt costs were choking off growth and threatening to bankrupt companies.

While the economy expanded by 4.5% last year, annual growth slowed sharply to 1.4% in the first quarter of 2025, according to Federal Statistics Service data.

Problems with Russia’s so-called two-track economy are accumulating, as its military-industrial complex benefits from massive state spending on the war while many private-sector businesses contend with slowing demand, rising costs and lower prices for exports.

Less documented is the growing strain on the banking sector after it granted favorable loans to help fund much of the Kremlin’s war effort and faces the burden of recouping those debts.

There has been a particular slowdown in the construction and industrial sectors and even some signs that the military side of Russia’s economy could be starting to stagnate, according to the people and documents.

There have been some public indications of concern about levels of bad debt.

A central bank report in May warned of “vulnerabilities of the financial sector” including “credit risk and concentration risk in corporate lending” as well as a “deteriorating loan performance” in consumer lending. Some 13 out of Russia’s largest 78 companies were unable to service their debt, double the number a year previously, the report said.

Still, the regulator said “the banking sector remains resilient overall,” while the ratio of problem loans in retail lending was “considerably lower” than in 2014-2016, when Russia was first hit by sanctions over Ukraine following Putin’s annexation of Crimea.

Russia’s ACRA rating agency warned in a report in May of “deterioration in the quality of loan debt.” About 20% of the entire banking industry’s capital is accounted for by borrowers whose creditworthiness is in danger of significantly decreasing due to high interest rates, the agency said.

Another paper the same month by the Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting, a think tank with close ties to Kremlin officials, found a “moderate probability” of a systemic banking crisis by April 2026. It warned the risk could rise if there continued to be a decline in the issuance of new lending and a further increase in poorly performing loans.